The Genetic Circuit Board of your Brain

Mental health is a topic that is often talked about but remains largely unknown.

When someone says mental health, “genes” or “genetics” is not the next immediate thing that comes to mind, maybe not even the fourth or fifth.

However, recent research into mental health urges us to think otherwise by establishing a significant genetic component for many mental health disorders.

These results can be crucial for understanding and treating mental health disorders.

Thinking about it logically, this shouldn’t surprise us at all!

The millions of activities in the brain contribute to our thoughts, emotions, love, consciousness, and so on.

Millions of brain cells or neurons transmit brain activities or signals.

So for effective brain activity, the brain cells must function well.

Each cell has DNA with thousands of genes. And if you have “normal” genes, your brain cells usually function.

However, if you carry a “change” or an “error” in one or more of the genes in the DNA of the brain cells, their functioning may be hampered.

Imagine an electricity grid; what’d happen if one circuit is flawed?

It may not result in a complete blackout, but we may face power fluctuations.

The brain is only 1000 times more complex! Minor changes may not entirely contribute to a mental disorder – there is no one “depression gene” or “anxiety mutation.”

But genetic factors make some people more likely to have mental health issues by interfering with the normal functioning of the brain cells.

This could explain why issues like depression or bipolar disorders seemingly run in the family.

Common Mental Conditions that have a Genetic Link

Depression and Genetics

Depression is one of the most common mental illnesses in the United States, with an estimated 15 million Americans affected yearly.

A growing body of research suggests that depression may be partly due to genes passed down from family members.

Studies have shown that depression is more common in families with a history of mental illness.

This suggests that there may be a genetic component to depression.

Heritability – the proportion of variation in a trait due to genetic factors – is estimated to account for about 40-50% of the risk for developing depression.

Glutamate Receptors and Mood Disorders

Years’ worth of research shows that glutamate is instrumental in depression.

There is also increasing evidence of a possible relationship between glutamate and the pathophysiology and treatment of depression.

Glutamate is a neurotransmitter (or chemical messenger) released in the brain that is important for learning and memory.

Excessive glutamate release in the body may be associated with excitotoxicity-induced brain damage.

Glutamate is synthesized in the body and ingested from certain kinds of food, including meat, cheese, and food seasonings containing MSG or monosodium glutamate.

High levels of glutamate have been linked to mood disorders like depression.

Glutamate receptors play a role in determining the levels of glutamate.

People with certain changes in the gene coding for glutamate receptors may be more prone to depression than others.

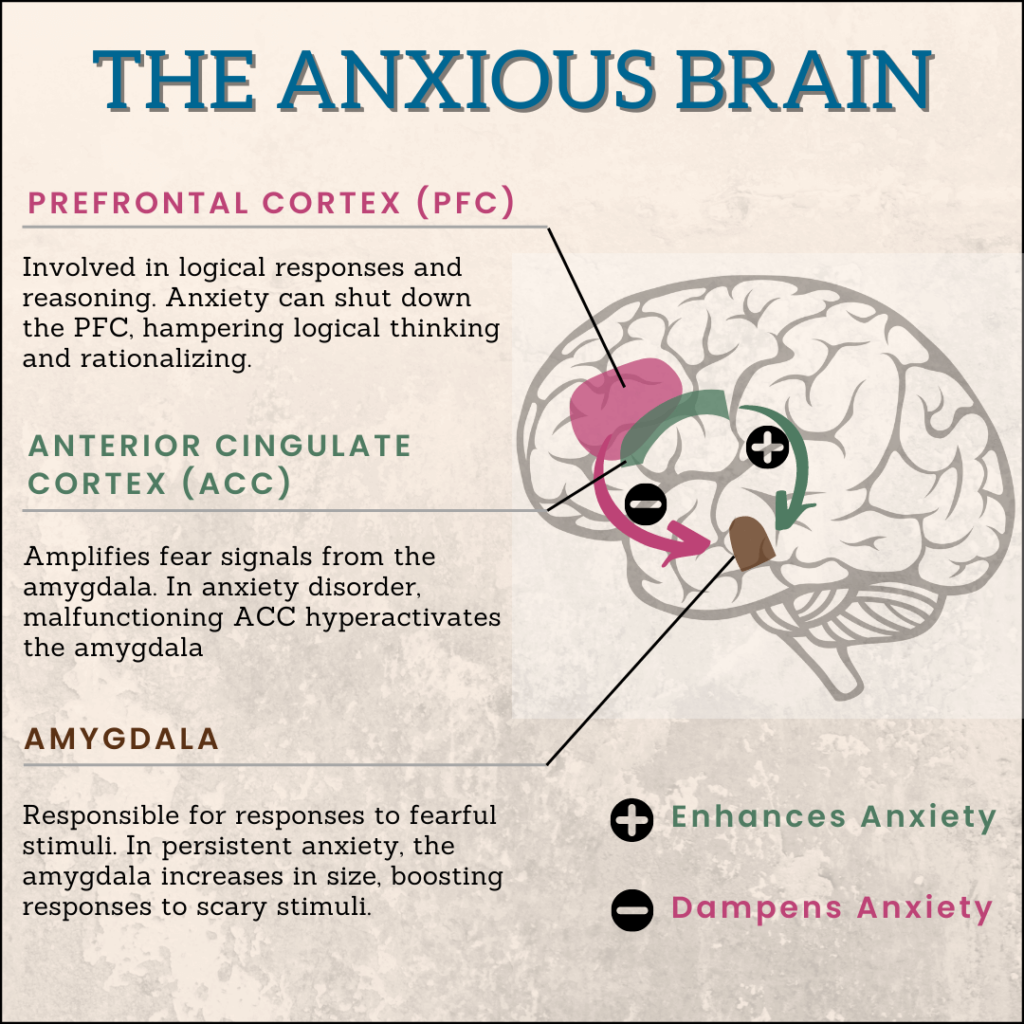

Anxiety and Genetics

Evidence-based studies reveal that anxiety, in part, is dictated by our genes.

Experts noticed a connection between genes and anxiety before discovering the role of DNA and genes.

If you have an immediate relative with anxiety, there are 2 to 6 times increased risk of developing it.

The serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT) is one of the well-researched genes for anxiety.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter or a brain chemical.

It is believed to be a mood stabilizer, which can aid healthy sleep patterns and boost your mood.

The 5-HTT gene is a crucial regulator of serotonin levels in the brain.

A clear correlation has been established between low serotonin levels and increases in depression, anxiety, and other mental health challenges.

The 5-HTT gene comes in two forms: L and S.

The S form is associated with lower 5-HTT gene expression and, subsequently, lower serotonin reuptake.

This results in an increased risk for anxiety.

Stress Response and Genetics

Before starting on the genetic link to stress, it is important to know that stress is not always a villain.

There are two types of stress: eustress and distress,

Most of us know that distress is a negative feeling characterized by extreme sorrow, sadness, and pain – bad stress.

Eustress is a positive form of stress that produces positive feelings of excitement, fulfillment, meaning, satisfaction, and well-being.

One of the most important genes connected with your stress response is COMT.

The COMT gene produces the catechol-O-methyltransferase or the COMT enzyme.

COMT breaks down neurotransmitters like epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine.

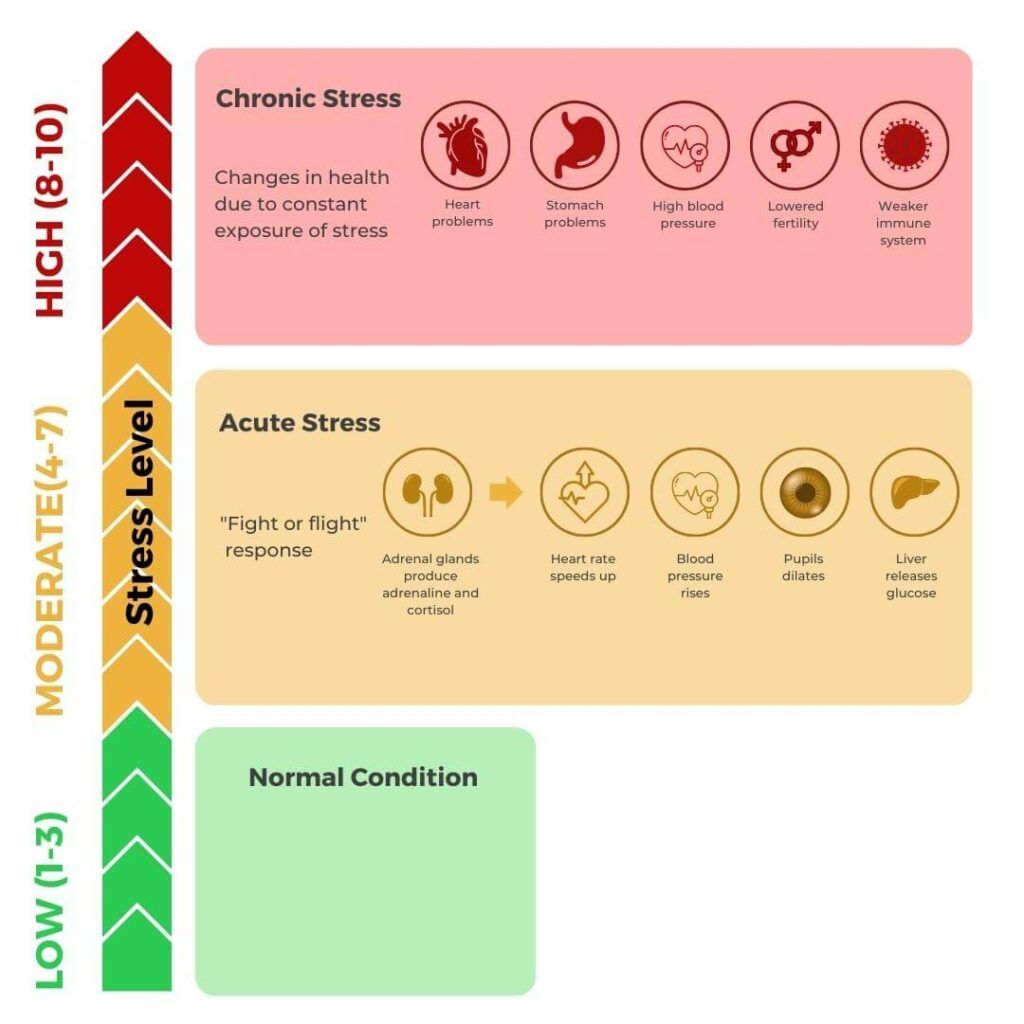

Your fight or flight response is activated in response to excessive stress and is triggered by epinephrine and norepinephrine.

Dopamine plays a crucial role in reward response.

A selected COMT gene modification called rs4680 or V158M has been proven to bring about changes in intellectual and behavioral traits and other illnesses.

People with the GG version of the COMT gene tend to have low dopamine levels and perform better under stress.

Those with the AA version tend to have lower stress resilience.

Genetic Testing For Mental Health

Xcode Life’s genetic test analyzes genes associated with mental health, like the ones mentioned above.

With the results, you can understand your risk for various mental conditions, including but not limited to depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, stress, and anorexia.

The reports also include customized recommendations to improve your mental health.

References

- Metabotropic glutamate receptors in the control of mood disorders

- Glutamate and depression: Reflecting a deepening knowledge of the gut and brain effects of a ubiquitous molecule – PMC

- Genetics of generalized anxiety disorder and related traits – PMC

- Association of the 5-HTT gene-linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with psychiatric disorders: a review of psychopathology and pharmacotherapy – PMC

- Genetics of stress response and stress-related disorders – PMC