With over 6 million people affected by GERD globally in 2019—an alarming 77.19% increase from 3.4 million in 1990—the prevalence of this troubling condition is rising rapidly. GERD, characterized by the reverse flow of stomach acid into the esophagus, is a widespread health concern with significant genetic influences. Research suggests that hereditary factors play a major role in an individual's risk of developing GERD. Knowing how genetics play a role is vital for managing and potentially avoiding this chronic disease. Keep reading to discover how your genetics might impact your risk of GERD and how this knowledge can inform your health choices.

What Causes GERD?

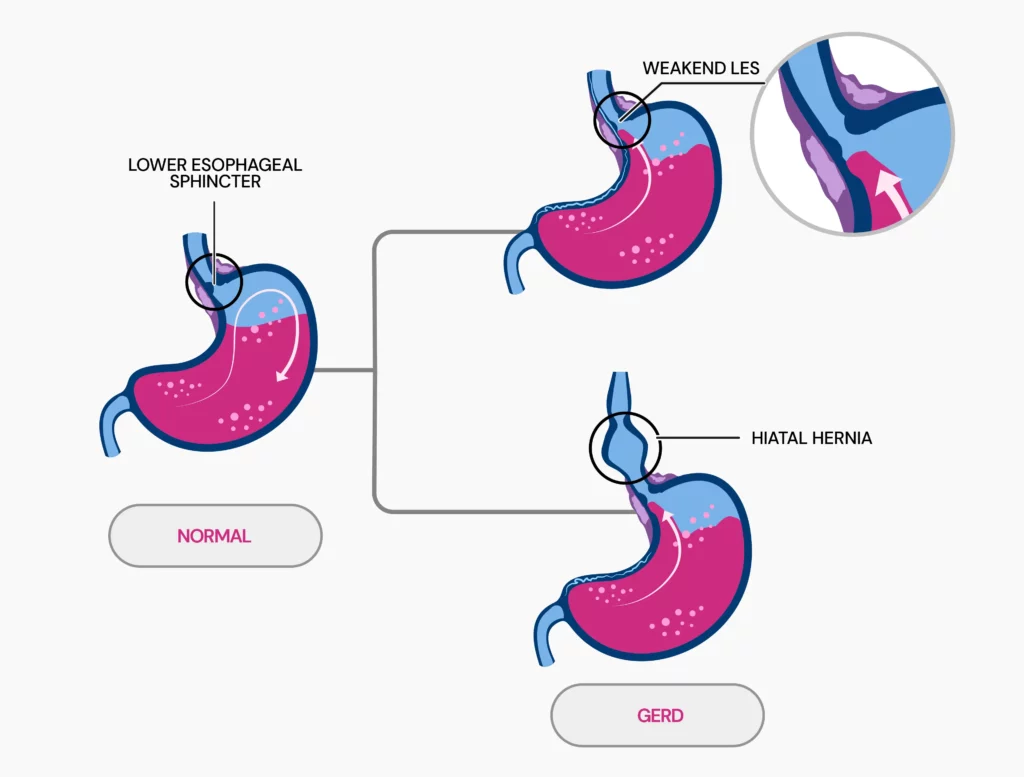

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when stomach acid flows back into the esophagus.

This occurs due to a problem in the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a muscle ring that separates the esophagus from the stomach.

Normally, this ring opens to allow food into the stomach and then closes to prevent the stomach's contents from flowing back up.

In GERD, the LES is either weak or relaxes when it shouldn't, allowing acid to move up into the esophagus.

Fundamental causes of GERD:

- Weak or relaxed LES

- Hiatal hernia, causing the stomach to push through the diaphragm

- Obesity and pregnancy, which increase abdominal pressure

- Certain foods (e.g., spicy or fatty foods) and habits (e.g., smoking, lying down after eating)

- Medications that weaken the LES or increase acid production

What Is The Most Common Cause Of GERD?

The most common cause of GERD is a weak or relaxed LES.

When the LES becomes weak or doesn't function properly, stomach acid is permitted to flow back into the esophagus, resulting in the symptoms associated with GERD.

Is GERD Hereditary?

Yes, GERD can be hereditary. Research reveals that genetic factors play a significant role, with a heritability rate of about 31%.

Certain genetic markers, like specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), are linked to a greater risk of developing GERD.

What Genes Play A Role?

Several genes are linked to GERD. Key genes include:

- FOXF1: Involved in developing gastrointestinal smooth muscle and regulating the LES.

- MHC: Associated with immune system responses and inflammation.

- GNB3: Related to cellular signaling.

- CCND1: Involved in cell cycle regulation.

Genes like COX-2, IL-10, GSTP1, XRCC1, hMLH1, and A61G are also associated with increased GERD risk due to their roles in inflammation, DNA repair, and growth factors.

Can Acid Reflux Run In Families?

Yes, acid reflux, also known as GERD, can run in families. A twin study provides strong evidence for a genetic component in GERD.

The study examined 1960 twin pairs, including both identical (monozygotic) and fraternal (dizygotic) twins.

Identical twins, sharing the same set of genes, were more likely to have GERD than fraternal twins, who share only half their genes.

The study indicated that monozygotic twins had a GERD symptom rate of 42%, compared to 26% for dizygotic twins. This suggests a significant genetic influence on GERD.

The study’s heritability estimates indicate that around 43% of the variance in GERD risk is due to genetic factors.

This suggests that having family members with GERD increases your chance of getting it, pointing to a strong genetic influence.

Other Risk Factors For GERD

Several conditions and lifestyle factors can increase the risk of GERD. Key contributors include:

Underlying conditions:

- Congenital disability (e.g., esophageal atresia)

- Previous chest or upper abdominal surgery

- Connective tissue disorders (e.g., scleroderma)

Lifestyle factors:

- Delayed stomach emptying

- Smoking

- Overeating or late-night meals

- Alcohol consumption

- Coffee consumption

- Aspirin use

- Excessive body mass index (BMI)

- Less physical activity

- Older age

- Emotional distress (e.g., anxiety and depression)

Is GERD A Lifelong Disease?

Yes, GERD is often a lifelong condition. It’s a chronic problem, which means that even if symptoms improve with treatment, they often come back when treatment stops.

People with severe GERD, like those with erosive esophagitis, usually need long-term treatment to keep the symptoms under control and prevent complications.

Studies have shown that after stopping treatment, up to 90% of people with healed erosive esophagitis see their symptoms return within 6 to 12 months.

This shows that GERD doesn’t go away easily and often requires ongoing management.

Treating GERD

Lifestyle changes often serve as the first line of treatment for GERD. If these adjustments are insufficient, further medical intervention may be necessary.

Over-the-counter options:

- Antacids like Tums and Rolaids can provide quick relief by neutralizing stomach acid but won't heal damage to the esophagus.

- H-2 blockers like Pepcid AC and Tagamet HB lower acid production for up to 12 hours.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like Prilosec and Nexium are stronger acid blockers that help heal the esophagus.

Prescription treatments:

- Prescription-strength PPIs, such as pantoprazole and esomeprazole, provide stronger acid control but can cause side effects such as headaches or low magnesium.

- Prescription H-2 blockers, such as famotidine and nizatidine, reduce acid with generally mild side effects.

Surgical options:

- Fundoplication is a procedure that wraps the upper stomach around the lower part of the esophagus to prevent reflux.

- LINX device, a ring of small magnetic beads, is implanted to block acid reflux while allowing food to pass.

- Transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) tightens the lower esophageal sphincter without surgery using an endoscope.

For obesity-related GERD, weight-loss surgery may be recommended.

Note: Always seek advice from a healthcare professional before starting any treatment or medication for GERD to ensure it's the right approach for your condition.

Preventing And Managing GERD

Dr. Yalini Vigneswaran, MD, MS, a gastrointestinal surgeon at the University of Chicago Medicine, offers expert advice on managing and preventing GERD, including:

- Eating slowly and controlling portions helps avoid pressure on the LES.

- Allowing 1-2 hours between eating and bedtime supports better digestion.

- Carbonated drinks and alcohol may relax the LES and increase the risk of acid reflux.

- Drinking water helps clear the esophagus and maintain acidity levels.

- Identifying and avoiding personal triggers like garlic, raw onions, chocolate, red wine, peppermint, and citrus fruits can help manage symptoms.

- Staying upright after meals aids digestion and reduces reflux occurrences.

Summary: Is GERD Hereditary?

- GERD can indeed be hereditary, with genetic factors contributing approximately 31% to its risk.

- Key genes linked to GERD include FOXF1, MHC, GNB3, and CCND1, which are involved in various processes, such as regulating the LES and immune responses.

- Research, including twin studies, supports a significant genetic influence on GERD, showing that identical twins have a higher rate of GERD compared to fraternal twins.

- As GERD tends to be a chronic condition requiring ongoing management, understanding its genetic links is vital for effective risk management.

Others Are Also Reading

Is Lupus Hereditary? An Overview of Genetic Factors

How It Works: Are Freckles Genetic?

Is Handedness Genetic? What Science Tells Us

References

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9122392

https://www.webmd.com/heartburn-gerd/reflux-disease-gerd-1

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/14085

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6107529

https://gut.bmj.com/content/52/8/1085.full

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17019-acid-reflux-gerd

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6140167

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1936305

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gerd/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20361959