Did you know that humans were never meant to digest lactose? A mutation that appeared thousands of years ago allowed humans to digest lactose and has been passed down ever since. Today, 70% of the world remains lactose intolerant, experiencing extreme digestive discomfort from dairy. This article will explore the genes behind lactose intolerance, explaining where the mutation came from, how it works, and what you can eat with a lactose-intolerant gut.

WATCH: How genes influence your risk for lactose intolerance

What Is Lactose Intolerance?

Lactose intolerance occurs when lactose is not digested well by our digestive system due to reduced or non-production of lactase enzymes.

Lactose is a healthy carbohydrate commonly found in milk and milk products.

It consists of two sugar units: glucose and galactose.

Lactose improves the absorption of calcium, which is essential for bone health.

Lactase is the enzyme in our body that breaks down lactose.

A deficiency or defect in this enzyme would prevent lactose from being digested, leading to primary lactose intolerance.

Secondary lactose intolerance is due to an illness or an injury that affects your small intestine.

Celiac disease and Crohn’s disease are common diseases affecting the intestine and impacting lactase secretion.

When lactose-intolerant people consume dairy products, they usually experience unpleasant gastrointestinal symptoms.

Some of the symptoms that occur immediately include:

- Cramps in the abdominal region

- Bloating

- Diarrhea

- Indigestion

- Gas

Is Lactose Intolerance Genetic?

Yes, lactose intolerance is primarily influenced by genetics, which determines how much lactase, the enzyme responsible for digesting lactose, is produced in the body.

This condition can manifest in various forms, with primary lactose intolerance being the most common.

In this case, individuals typically produce sufficient lactase during infancy but experience a decline in lactase production as they age, leading to difficulties digesting dairy products.

Additionally, congenital lactose intolerance is a rare genetic disorder where infants are born without the ability to produce lactase at all.

Understanding these genetic factors helps explain the varying degrees of lactose intolerance across different populations and age groups.

The LCT Gene

The LCT gene produces the lactase enzyme, which degrades the lactose molecules.

Another gene on chromosome 2 called MCM6 controls the LCT gene.

One portion of this MCM6 gene, known as a regulatory element, helps control the amount of lactase the LCT gene can produce.

rs4988235

This RSID denotes a mutation in the MCM6 gene, which controls the amount of lactase produced.

The most common allele in this position is T.

It enables lactase production in proportion to the number of T alleles present.

A person with two T alleles (one from each parent) will produce more lactase than someone with one or no T alleles.

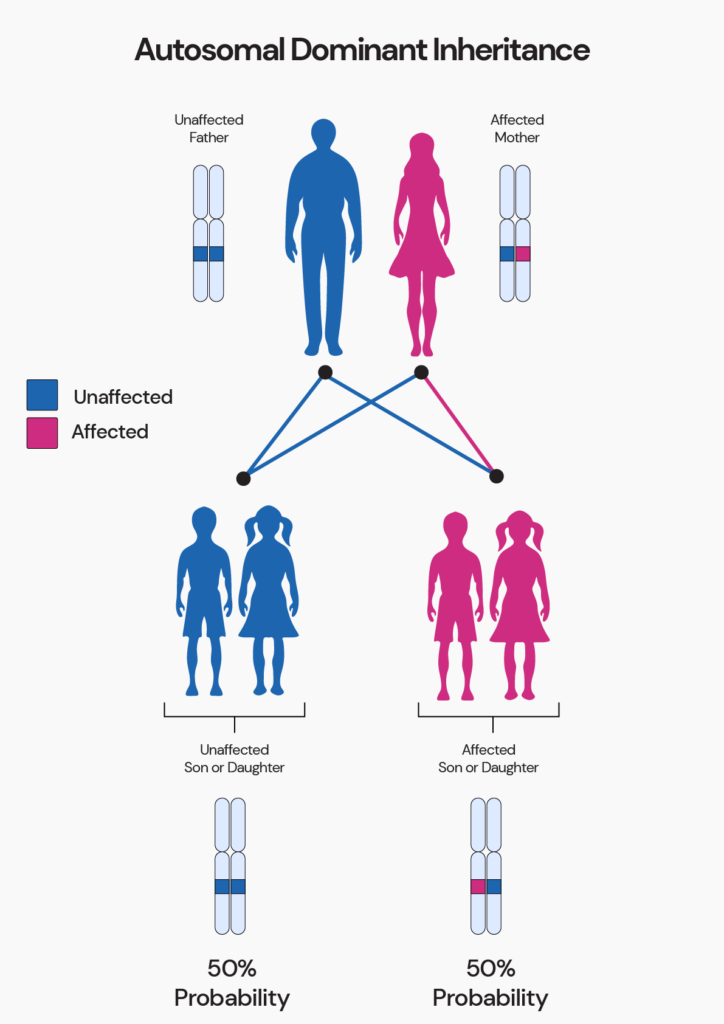

Inheriting Lactose Tolerance

The lactose tolerance or persistence trait is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.

It means that if any of your parents are lactose tolerant, you will be too.

This dominant inheritance pattern helps explain how the trait spread far and wide over generations.

Lactose intolerance is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.

This is why it’s prevalent within communities.

How Did Humans Develop Lactose Intolerance?

Animals can only digest milk in their infancy while their mothers nurse them.

As they grow, their bodies gradually stop producing lactase.

Thus, the entire animal kingdom, except humans, is naturally lactose intolerant.

Around 8,000 years ago in present-day Turkey, humans had just started to domesticate and milk cows, goats, and sheep.

The lactase gene LCT mutation appeared more frequently, imparting lactose tolerance to humans.

Initially, only a few humans had this mutation.

During times of famine, milk was the only nourishment readily available.

Those who could digest lactose survived and passed on the gene to their descendants.

Can You Suddenly Become Lactose Intolerant?

Imagine a person who’s been following a vegan diet.

Since he doesn’t digest lactose, his body stops producing lactase.

The cells responsible for lactase production disappear temporarily due to disuse.

This explains why a genetic test could indicate intolerance despite no history of lactose intolerance.

If he consumes a dairy product, he will likely experience symptoms of lactose intolerance.

This is because the lactase-producing cells need to reactivate and proliferate.

The Role Of Gut Bacteria

Certain bacteria in our gut flourish in the presence of lactose and help break it down.

This is why many lactose-intolerant people can still have a cup of milk (12 grams of lactose) without experiencing any symptoms.

This could also explain why a person can consume dairy despite a genetic test indicating lactose intolerance.

Ethnicity and Lactose Intolerance

The incidence of lactose intolerance varies among different population groups.

East Asians are the most lactose intolerant population, with 70-100% of people affected.

On the other hand, North Europeans have an incidence of 18-26%.

Their ancestors had a culture of dairy farms and consumed unfermented dairy products, passing on the gene type that produces lactase.

Ethnicity also influences the age of onset of lactose intolerance.

In Finland, 1 in 60,000 newborns are affected, the highest incidence in infants worldwide.

In African-American populations, most children develop intolerance by the age of two.

Caucasian children become intolerant after five years of age.

Lactose Intolerance-friendly Diet

A lactose-free diet is the best way to combat lactose intolerance.

Before eliminating lactose from your diet, you should test the extent of your intolerance.

Research suggests that many people can have a cup of milk daily (12 grams of lactose) with barely any symptoms.

Lactose-digesting bacteria in your gut can sometimes substitute for lactase.

Some lactose intolerance therapies involve introducing new lactose-digesting bacteria into the gut.

Since dairy is rich in Vitamin D and calcium, it’s best to have a cup of milk if you can tolerate it.

But even if a hint of lactose in your diet puts you in trouble, you should eliminate dairy and all other sources of lactose.

What Can You Eat?

Some healthy food groups that are also lactose-free include:

- Fruits and Vegetables

- Seafood

- Lactose-free milk: Almond milk, soy milk

- Eggs

- Legumes

- Nuts and Seeds

- Whole grains

Meeting Your Calcium And Vitamin D Requirements

Calcium and vitamin D are essential for your bone health.

Getting adequate levels of these nutrients on a dairy-free diet can be challenging.

Some food sources are naturally high in calcium and vitamin D.

Incorporating these foods into your diet can keep your bones healthy:

- Dark green vegetables like kale, broccoli, collarbeans, and bok choy.

- Almonds

- Fish with soft bones, such as canned salmon or sardines.

- Soy foods like tofu or soy milk.

- Unsweetened Orange juice fortified with vitamin D and calcium

- Chia and poppy seeds.

- Lactase supplements, lactose-free vitamin D, and calcium supplements -

Modify your diet only after consulting a doctor.

Summary: Is Lactose Intolerance Genetic?

- Lactose intolerance is an inability to digest dairy products, affecting 70% of the population.

- Primary lactose intolerance prevents the production of lactase, an enzyme that digests lactose.

- Secondary lactose intolerance is due to illnesses or injuries that damage the intestine, the site of lactose digestion.

- Ethnicity can affect the severity and age of onset of lactose intolerance across populations.

- The LCT and MCM6 genes control lactase production and are dysregulated in lactose-intolerant individuals.

- A lactose-free diet with alternative calcium and vitamin D sources is the best way to adjust to lactose intolerance.

Others Are Also Reading

How It Works: Are Freckles Genetic?

Is Sleep Apnea Genetic? Risk Factors, Treatment, And More

Is Handedness Genetic? What Science Tells Us

References

https://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/news/070401_lactose

https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/mcm6

https://www.snpedia.com/index.php/Rs4988235

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3048992

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25625576?dopt=Abstract

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12602-018-9507-7

https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/lactose-intolerance/#frequency